Art imitates life. AI imitates art.

Why I'm an optimist about the future of art in the age of AI

This newsletter is a little different. I’m going to engage in some art criticism (the positive kind) even though I am not an artist. But I know there are some artists who read the newsletter. So, by all means, comment and let me know what I’ve gotten wrong or if there are better ways for us to think about this issue. I’d love to hear from you!

I read an Erik Hoel piece this week called, “Welcome to The Semantic Apocalypse.” It’s a powerful piece and I recommend it. In it, Hoel laments the recent Studio Ghibli revolution in generative AI.

If you haven’t seen the phenomenon for yourself, OpenAI recently released a generative AI feature that allows users to convert photos into, not just anime, but the specific style made famous by the anime movie studio called Studio Ghibli.

I’m not a big anime fan myself (to those who are, please forgive me), but even I have noticed people posting Studio Ghibli-style images and changing their profile pictures to Studio Ghibli-style avatars.

Hoel, in whose family life Studio Ghibli films have played a special role, argues that this is just the latest example of how AI cheapens art. This large-scale mimicry cheapens the original.

He might very well be right about that, but I want to explore an alternative. I think generative AI leaves me optimistic about the visual arts (as it does about good writing).

Our current AI moment is, of course, profoundly disruptive. There is a strange, yet perceptible, trend forming. I’ve had trouble trying to describe it, so maybe a metaphor will help. Do you remember when Michael Phelps—the twenty three time Olympic gold medal winner—seemed unstoppable as an Olympic swimmer? At times, it felt as though, in some obvious and deterministic sense, Phelps would win the gold, but then there were wide open questions about who would win the silver.

This is how I think about AI’s ability to create art: The kind of content that AI can produce isn’t gold medal content. But AI is really good at competing for silver.

OpenAI’s image generation model didn’t invent a new style of anime—that would be gold-medal art. AI is bad at gold-medal art. Instead, it drafted off the leader to position itself a second-place contender.

Generative AI is exceptional at mimicry, and I think Hoel is right to point out that this has a cheapening effect on some artistic expressions in some ways.

But AI that’s good at competing for second place, it seems to me, will create an army (ok, fine, a navy) of swimmers competing for silver. But, to torture this metaphor, I don’t think those second-place swimmers do anything to tarnish the accomplishment of the first-place winner.

Ok, I need to dispense with the metaphor now and focus on the visual arts. I want to make it very clear (as I promised I would in my first post), that I am by no means a visual artist nor an expert in the visual arts, but I did have an experience recently that I’d like to share with you.

I visited the Legacy Museum in Montgomery Alabama. It is a very well-designed museum and the experience was powerful. When my friends and I had made our way through the formal museum exhibits we found ourselves in a bright and well-lit art exhibit. The staff asked us not to take pictures or use our phones and I didn’t bring a pen and paper, so unfortunately, I couldn’t take notes and you’re just going to have to take my word for what comes next.

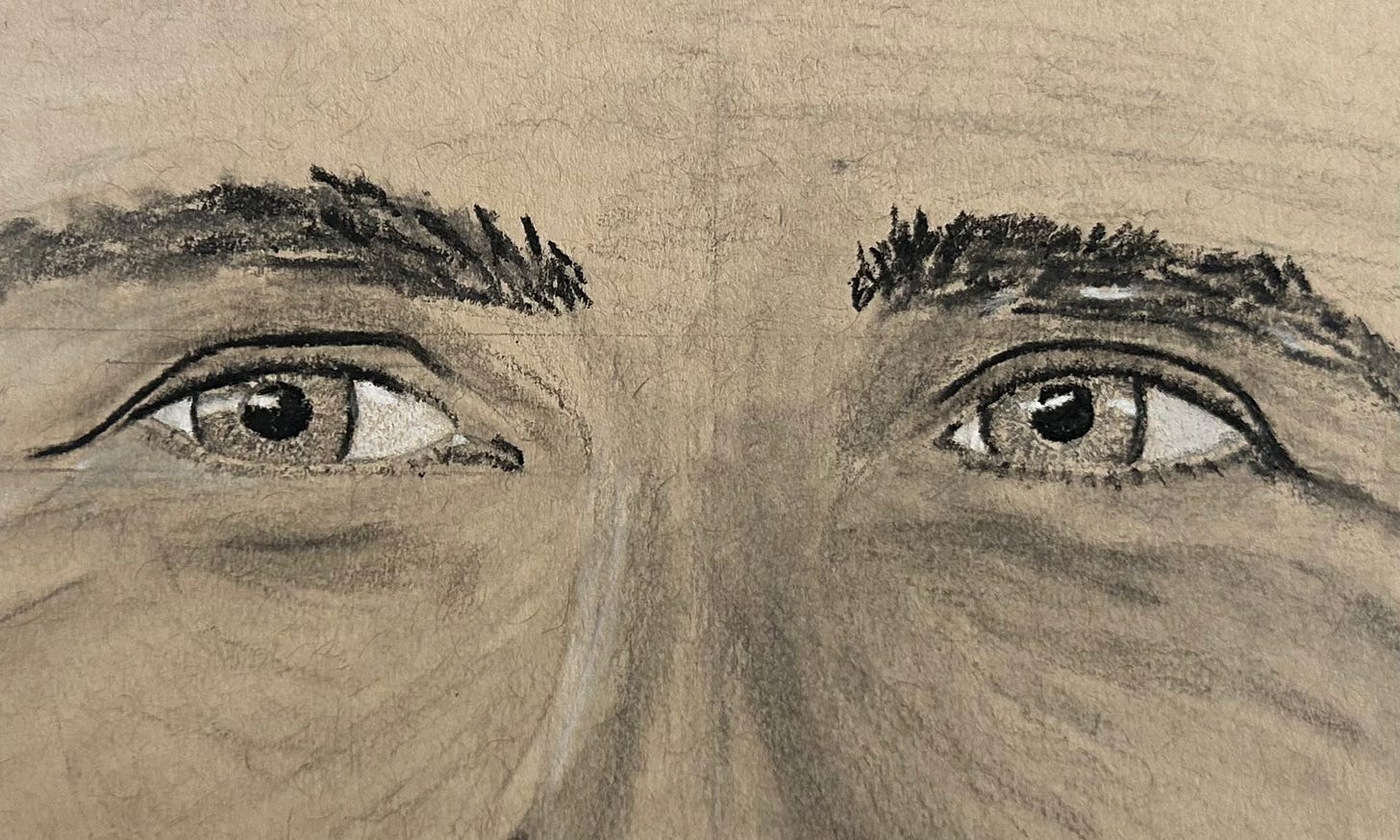

There was a large portrait of a middle aged woman’s face on a large canvas, probably six feet by four feet. I think the medium was oil on canvas. The artist intentionally draws the viewer into the subject’s eyes—the sharpest and most detailed element of the whole painting. And then, as the depth changes, the focus changes. Her ears, which, in our 3-D world, would be further from the viewer than her eyes are slightly—but just slightly—blurrier than her eyes. The tip of her nose, which is closer to us, is likewise just a little blurry. The further backward or forward one looks, the blurrier the painting becomes.

This should come as a surprise to no one in the age of ubiquitous photography. When photographers use a larger aperture (or a lower ƒ-stop setting), the selected object is in focus and everything else blurs. That’s one tool photographers use to direct their viewers’ eyes.

But it wasn’t the way the old masters drew the eyes of their audiences.

The 17th century Dutch master, Rembrandt, used light and place, rather than focus, to direct his viewer’s attention.

In “La ronda de noche,” or “the night watch,” (a massive oil on canvas painting I was able to see in person in 2023 amidst its re-framing at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam), the viewer’s attention is directed first with light and second with place. The two men who seem most to have a spotlight shone upon them are also the two men both centered in the frame and placed in the foreground. But look at the surrounding crowd. They are darker and we see less contrast in light and color, to be sure, but they are no blurrier than our two protagonists. Everyone in the frame—whether in the foreground or in the background; no matter how distance from the viewer—is equally sharp and focused.

And why, do you suppose, the Dutch master would paint in such a way? I think it’s because that’s how people appear to us when we look at them. Suppose you had stumbled upon the night watch crew in real life. And suppose, as your mind tried to take it all in, that your eyes darted from the two men foregrounded in the center to the man with the tall hat and the spear, and then to the drummer on the far right, and then musket-loader to the left. Each time you moved your eyes, the tiny muscles in your eye socket would have fixed your gaze on your subject—on your subject, not on Rembrandt’s. Then your pupil would have dilated or contracted to adjust for the light. At the same time, the very lenses in your eyes would have changed their thickness to bring your subject in to focus all in a fraction of a second.

You see, before the invention of photography, we did see clearly at every depth. That’s how our eyes work.

But unlike the flexible and malleable organic lenses in our eyes, camera lenses are made of glass, carefully crafted to a specific diameter and a specific thickness. And when the camera brings one depth into focus, it blurs the other depths as a matter of physics.

What happened to the woman in the portrait I saw at the Legacy Museum is exactly what happens in a traditional photograph. Remember the aperture and ƒ-stop I mentioned above? These are the settings photographers manually manipulate to create these effects of focus and blur. Mechanically speaking, the focus of the picture is defined by the diameter and thickness of the lenses and the distances between them. And, governed by the physical properties of photons passing through shaped glass, if the camera focuses on an object at some distance from the camera, objects at other distances—whether closer or further away—will become blurrier.

I took a photography class with my daughter not long ago and the instructor showed us this phenomenon in some of his own photography. In one photo, he showed us a picture of a frog on a lily pad in a pond surrounded by other lily pads.

See how the frog is in sharp focus, but the lily pads in the foreground and those in the background are blurry? But look at the lily pads just to the left or right of the frog. Those are just as sharply focused as the frog is. But why? Wouldn’t you think that the photographer, David Vives, would have wanted us to focus on the frog—just as the painter wanted me to focus on his subject’s eyes—and so wouldn’t Vives have made the frog sharp and all the surrounding image blurry?

That’s just it, though. Vives is not working in the land of make believe nor in the land of generative AI nor in the land of oil on canvas. Vives lives in the land of optics. The variables that define sharpness and blurriness are the diameters and thicknesses of the lenses and the distances between them. These variables remain the same, not just for the frog, but for the lily pads to its left and right which are just as far from the camera as the frog is—and this is true whether Vives wishes it to be or not.

There are facts about physics that have helped to define the field—even the artistic discipline—of photography. And now, at least in some narrow instances—certainly in the case of the painting I saw at the Legacy Museum—painting has come to mimic these physical properties.

Notice the order of operations here. The painting I saw at the museum was not art charting a course on its own, only loosely connected or even disconnected from our physical reality (like pointillism or surrealism might have done). The art I saw was intentionally imitating life—the painter chose to paint in such a way that the painting would look like a photograph.

I can only imagine how disruptive the invention of the camera was to the profession of painters and how painters must have felt as the technology became more commonplace.

My family and I visited George Washington’s Mount Vernon a few years ago. The person who stood in for Washington played the role convincingly. After a few minutes of discourse about 18th century agriculture, my wife asked if Washington could “take our picture.”

“Take… a picture, madam?” Washington asked, perplexed. “Where would you have me take it and why?” He kept the gag going until my wife asked him to use her device to “make a portrait” of our family.

This question is one that would have been equally baffling to Washington: If a machine can faithfully produce the image of the subject, what role could be left for the portrait painter?

Well, in this one (admittedly, very, very narrow sense), one role for the portrait painter was to continue to produce art, but to do so in a new way—in a way that takes at least some inspiration from the work of the machine.

Ultimately, even I (novice though I am) can recognize excellence in the visual arts when the artist makes no attempt to reflect the properties of optics and physical lenses; but I can also recognize excellence in the visual arts when the artist does attempt to reflect principles of photography.

Perhaps—perhaps—there is a similar future for the visual arts in the age of generative AI. Artists will continue to develop genuine innovations, just as Studio Ghibli has done, and the machines will mimic. But perhaps, just as painters might imitate the effects of photography, visual artists may learn to create real art, genuine art, that reflects in some way the properties of the machine-made art.

I make no claim to predict the future of AI (or of art), but I’m hopeful. I heard someone say once that the “AI” in “generative AI” stands for “Average of the Internet.” There’s an insight there. These machines that drive all outputs toward the average (or toward plagiarism, if you like) might make competition for second place stiffer, but I think they’re unlikely to produce gold medal art.

Ultimately, the great flattening that AI is doing to art, and that Erik Hoel justifiably laments, is real. But it invites artists to create art that breaks through that sea of flatness.