Efficient AI

Inefficient relationships

When I was about 8 years old, my family and a bunch of other families from my church participated in a jog-a-thon. We asked friends and neighbors to support us by pledging a certain number of dollars per lap that would ultimately go to the designated charity. Then, on the big day, we kids would run as many laps as our little legs would carry us. Then, our friends and neighbors were on the hook to donate what they had pledged.

The track we ran on was probably a standard quarter-mile, oval track. Like most seven year olds, I hadn’t taken geometry yet. As I started another lap on the large arc that was the end of oval the track, I thought to myself, “why should I bother running around this curved part? It would be much easier just to run straight across the field. That would get me to the end of this curve faster. It would save me some time, it would probably enable me to run more laps, and that would raise more money for the charity.” It was a pretty brilliant plan.

I told my older sister what I was thinking of doing. She advised against it. But at 7 years old, I was pretty sure I was smarter than everyone else. I took off across the field, turning a half circle (a distance of π*radius, or roughly 3*radius) into the diameter of that circle (2*radius). When I finished the lap, my dad pulled me over and told me that lap didn’t count because I had cheated.

I was genuinely confused. I didn’t think I had cheated. If the task was to go from point A to point B a bunch of times and I found a quicker way to get from point A to point B, why shouldn’t I take it? I wasn’t cheating. I was just getting the job done more efficiently.

With the benefit of hindsight (and high school geometry), I can see now where I went wrong. I was supposed to run as many quarter-mile laps as I could. But literally cutting corners, I had changed the lap into something less than a quarter mile. It’s not that I was doing the task differently from everyone else. I was doing a different task—and it’s not the task the donors had in mind when they made their pledges.

I want to pull us over here—like my dad pulled me over on the track—for just a minute. It isn’t that I cheated, not exactly. I think “cheating” requires an understanding of the rules and an intention to break them for one’s own advantage. I wasn’t cheating, but I was searching for an efficiency play on a task where the efficiency play was inappropriate. That is, optimizing for efficiency—as my 7-year-old mind was trying to do—defeated the purpose of the jog-a-thon. After all, if we were really trying to optimize for efficiency, the best thing to do would be to stay home and ask people just to donate cash. But by participating in a jog-a-thon, we were abandoning efficiency for something else—activity, participation, effort, will power, exercise—lots of things, maybe, but not efficiency.

I think we’re at a similar point in the development of generative AI. At present, generative AI is optimized for the efficiency play. Companies around the world are selling Generative AI tools to help us to do what we were going to do anyway, but faster, or cheaper, or with a smaller workforce.

But there are areas of life that the efficiency play doesn’t work. My own family had fallen into a bit of a sump according to which we grab our dinner then head for the basement to watch TV. It’s pretty efficient. We eat dinner. We consume entertainment. What’s not to love? The problem had nothing to do with efficiency; it had to do with quality. We’ve eliminated that routine from our lives almost entirely. Now we eat dinner at the table. Then my wife and I read classics to the kids (at present, it’s The Horse and His Boy and Robinson Crusoe).

It’s not efficient. Relationship-building is almost never efficient.

I spent the summer of 2010 on Kandahar Air Field, Afghanistan. Each Saturday, base security would permit local tradesmen to sell their wares on the base—everything from Afghan rugs (which I definitely bought) to Chinese bootlegs of the entire Seinfeld series on DVD (which I also absolutely bought). I worked seven days a week on the midnight shift; so it was non-trivial for me to wake up Saturday morning and visit the bazaar, but I liked to do it because it helped me to mark each passing week.

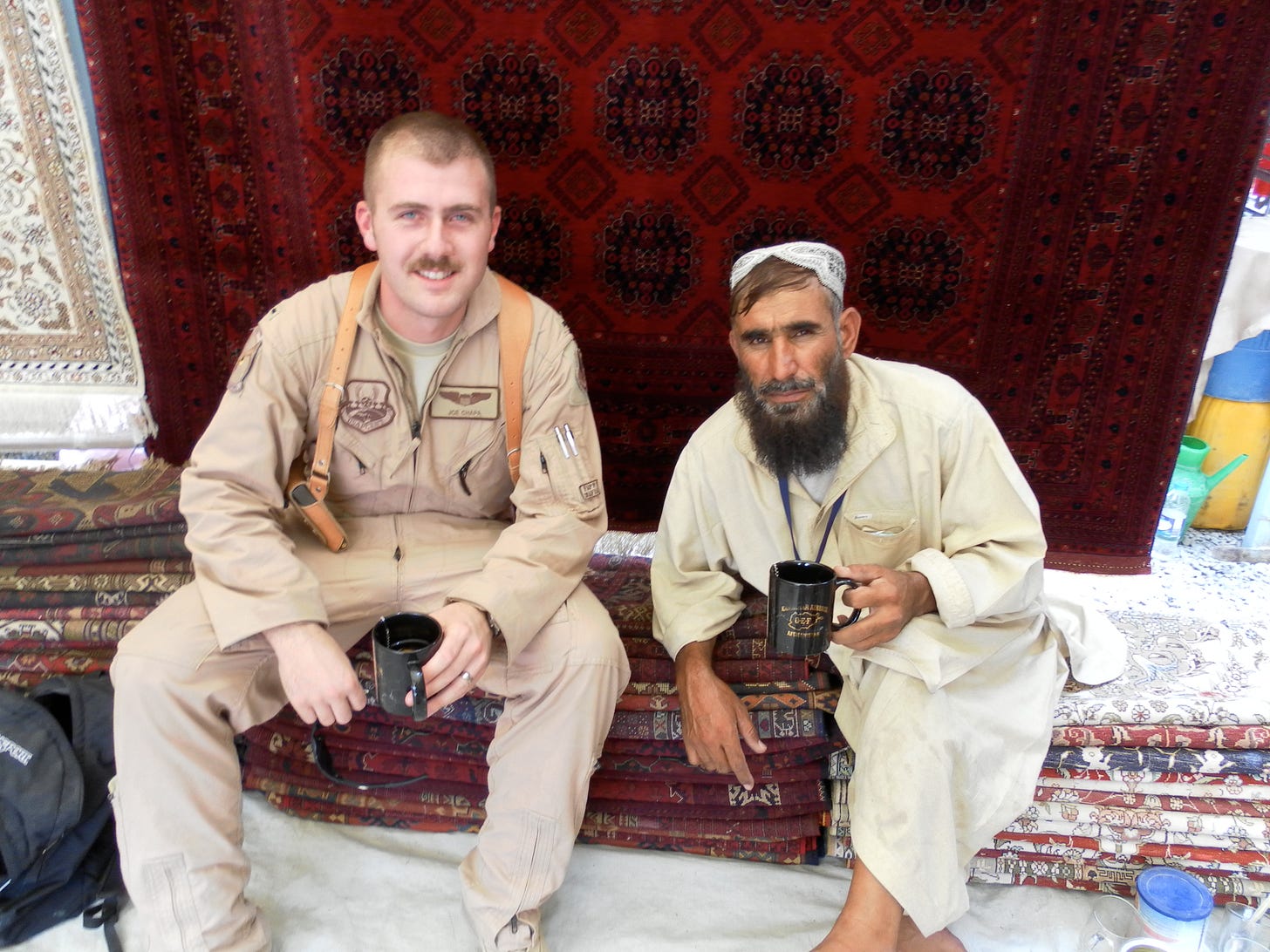

I befriended one of the rug salesmen, a man named Mohammed. He offered me tea and I accepted. We talked about his family and mine. We talked about his work (I talked very little about mine). And he made us tea every week. So confident had I become in this tradition that I wrote home to my wife and asked her to send me loose leaf tea, an electric kettle, and an insulated thermos. I bought two “Operation Enduring Freedom” coffee mugs from the BX and, when the rest of the kit arrived, I made tea on the floor of my room, next to my bunk, packed it all in a backpack and left for the bazaar.

When I arrived, Mohammad gestured his offer to make tea. I said, “no, no, it’s ok. I brought tea.” Mohammad’s son translated my statement for his father. Mohammad’s eyes grew wide, and he responded in English “You brought me tea??”

Then we sat down and we each took a sip of the makeshift tea I had brought that had already gotten cool.

Mohammad took the number of sips he felt that courtesy demanded of him. After a long silence, he looked me in the eye and said in strongly accented English, “I make tea?”

There was nothing efficient about my (failed) attempt to make tea for Mohammad. But relationships aren’t about efficiency.

I know there are important ways that machines may be able to fill the roles that humans ought to fill in some extreme circumstances (I’ve written about that here). But more generally, I think we should be wary about inviting AI into our relational lives.

There is already a market for this sort of thing—AI significant others; AI friends; AI social companions—and tech startups are unsurprisingly rushing to meet that demand. But I think we should resist that temptation. AI is very good at efficiency. But efficiency is bad for relationships.

Credit Where It’s Due

Views Expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the US Air Force, the Department of Defense, or any part of the US Government.

So true!