Plato Had Some Thoughts on LLMs... Sort Of

What a 4th century BC philosophy can teach us about 21st century chatbots

The global AI phenomenon we are all living through began in 2022 when OpenAI launched ChatGPT, a chatbot based on a large language model called GPT-3. Within months, ChatGPT had gained 100 million users, making it the fastest-adopted technology in human history.

But why did ChatGPT see such wide adoption so fast? What is it about ChatGPT that resonated so strongly with us human users? ChatGPT wasn’t the first AI tool. It wasn’t the first large language model. It wasn’t even the first chatbot. So, what made ChatGPT so special?

Perhaps the best explanation for ChatGPT’s rapid global adoption is that it showed, for the first time, that machines can engage in dialogue.

Humans developed language about 250,000 years ago, but invented writing only about 5,500 years ago. The ancient Greek philosopher, Plato, wrote from a peculiar vantage point in the linguistic drama. He wrote about spoken and written language just 2,600 years after it was invented. Plato wrote about writing during writing’s very adolescence.

The only Platonic writing that remains are his dialogues between Socrates and one or more interlocutors. In one such dialogue, Socrates’ friend, Phaedrus, has just come from hearing a famous orator speak. Phaedrus wants to try to reproduce the speech from memory, but Socrates sees that Phaedrus has a copy of the written speech. Socrates insists that Phaedrus read the speech instead because, with a written copy of the speech in hand, it is as though the author “is here present.”

This is Plato’s first volley in a back-and-fourth discourse—dialogue—about the value of language. His first observation: written language is valuable because it can preserve accuracy. But the discussion continues.

By the end of the dialogue, Socrates and Phaedrus come to a powerful conclusion about the value of language—especially in the form of a dialogue.

Once language is fixed in writing, Socrates says, it is dead language. He says it is like a painting of flowers. It might look like it’s alive, but it cannot grow. A dialogue is better because it is alive. It flourishes as participants feed and tend to it.

Haven’t we all experienced this power of dialogue—late into the night around the kitchen table with heavy pours of cheap wine or on the back porch with cigars smoked to the nub. We cannot have known in advance where the conversation would take us. We each feed the dialogue and nurture it. And in the morning, long after the bottles are empty and the cigars are snuffed out, we can neither precisely recall nor reproduce what was said. We know only that what we experienced was beautiful because it was alive.

This distinction between dead language and living language is not merely academic for Plato. How will he ultimately pass down his philosophy? He must write it down to preserve it. But when he does, he writes in the form of a dialogue. He gives us the dead language of the written word, but he has done everything he can to capture the power of living language that two or more can create together.

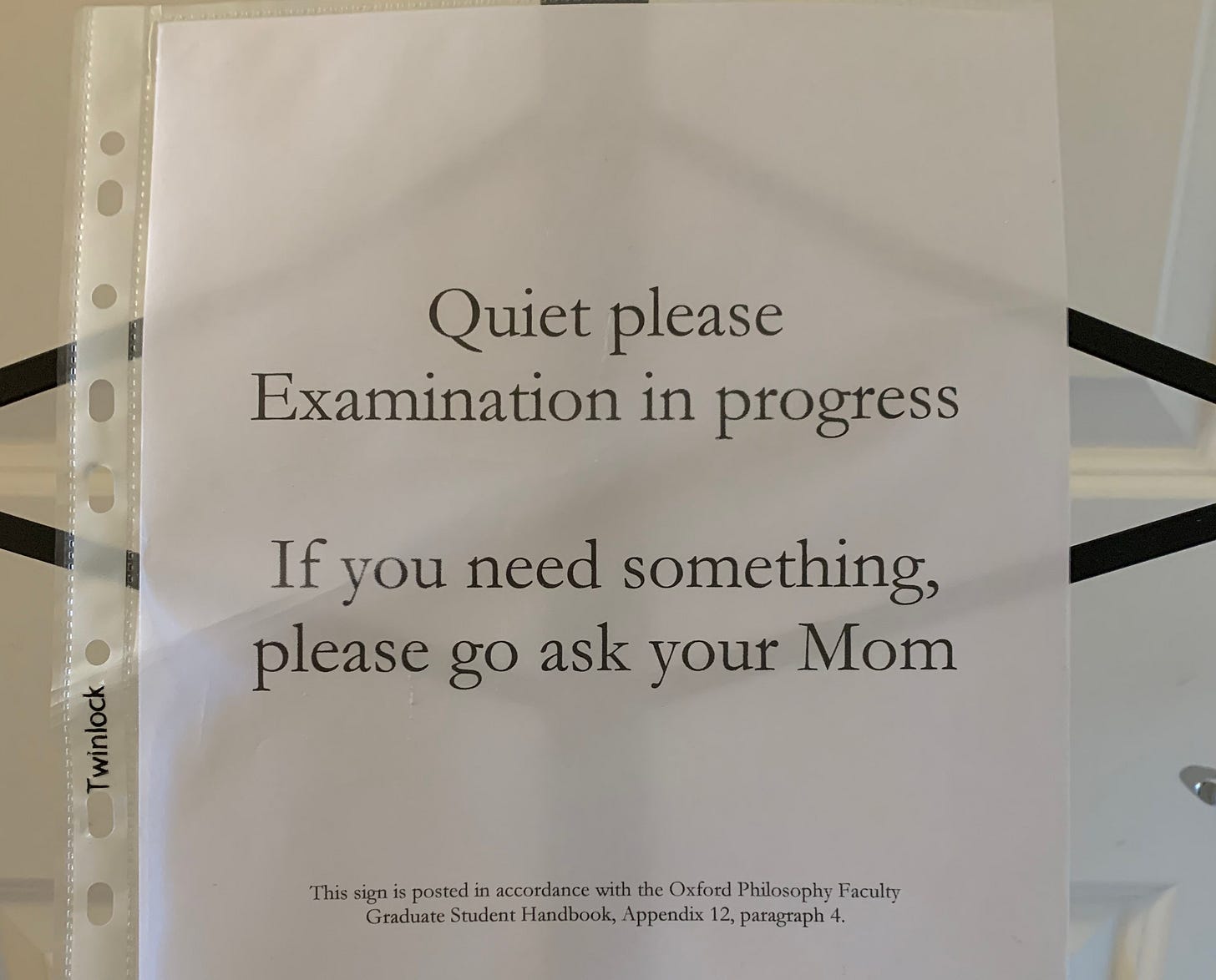

I defended my doctoral thesis at Oxford—an event called a “viva voce”—amidst pandemic lockdowns. “Viva voce” in Latin is, quite literally, the “living voice.” The exam is, and always has been, an oral defense. It is a dialogue between the examiners and the examined. It is living speech between the participants.

Oxford is, quite literally, old school and though the university did allow for vivas via video calls during the pandemic, it did not rescind any of the other rules surrounding its hallowed vivas. In accordance with the Philosophy Faculty Graduate Student Handbook, I was required to place a sign outside the “exam” (that is, outside my home office) saying, “Quiet please. Examination in Progress.”

Alright, back to Plato.

Plato’s distinction between dead language and living language applies to modern AI with startling implications. We humans have a relatively shallow repository of spoken human language. But in a quarter century of internet use, we have compiled a behemoth repository of written human language. The seismic shift in AI development over the last two decades has been based on, among other things, the ability to use these massive text repositories as training data for large language models.

This is the twist in the AI language drama: We humans developed dialogue some 250,000 years ago, and only much later did we invent writing. AI, on the other hand begins with the text we invented—mountains of data on the internet. But through interactions with our written language, AI models have learned to dialogue. Or, in Plato’s terms: We humans started with live language (dialogue) and then invented dead language (writing). AI starts with dead language (writing) and then learns to participate in live language (dialogue).

We now live in a world in which machines can participate in what Plato saw as living speech. And this is not a risk-free proposition. In the battle between “in real life” experiences and online facsimiles, dialogue could become just one more casualty—a deeply human experience lost to the digital world. Then again, those moments late into the night around the table or on the porch are rare. Maybe there is little harm and much to be gained by engaging in living language with machines in between those deeply human moments.

I’m not sure about this, but it deserves more thought. Maybe I’ll stay up late into the night and discuss with friends over wine and cigars. Who knows where the live language will take us?

Credit Where It’s Due

As always, the Views Expressed are my own and do not necessarily reflect those of the US Air Force, the Department of Defense, or any part of the US Government.