Slow Down to Speed Up

Employing GenAI and employing GenAI well are not the same thing

First things first: this newsletter is a labor of love and sometimes, producing the text, the audio, and the sketch is a lot to accomplish each week. This week, I almost didn’t get it done. So I did what any normal person would do in 2025, I turned to ChatGPT. I fed the model about a dozen of my sketches and then asked it to produce an image of an aircraft clock in the style of my own charcoal sketches. It did a good job. It did a great job, actually. Well, fortunately for you (and for my integrity as an artist), my flight was delayed, so I did have time to finish my own charcoal sketch of the aircraft clock.

But listen, the ChatGPT clock was really good. I’m almost embarassed to share with you my rubbish aircraft clock now that I’ve seen what ChatGPT can do. BUT I made a commitment. One post per week with a sketch to match. So here you have it, my post and my sketch (which is far worse than the ChatGPT sketch).

There saying among pilots: “Slow down to speed up.” The idea is that when things go bad in an airplane—an emergency light flashes on the illuminator panel, you hit a bird, you lose an engine—there is a real risk tharenaline will overpower reason and cause the pilot to do utterly stupid things. Instead, the pilot should “slow down to speed up.” Or, as other instructor pilots put it, “slow is smooth and smooth is fast.” Or some instructors tell students to “wind the clock.” (This one is pretty anachronistic because modern airplanes don’t have clocks that require winding anymore. But in the old days, when something went wrong, sometimes, the best way to prevent reacting in a stupid way was to take a moment to wind the clock).

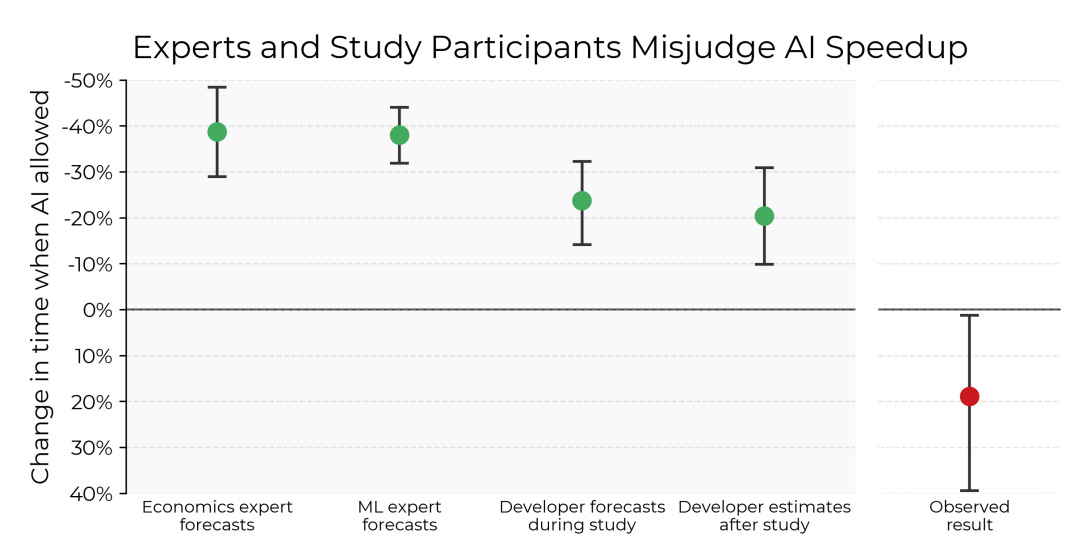

Researchers at Model Evaluation and Threat Research (METR) published a paper recently to suggest that, when it comes to using AI in coding, maybe developers should “slow down to speed up.”

I can’t speak to the veracity of the study. It’s not published in a journal. As far as I can tell, it’s just sort of out there on the interwebs, so buyer beware. But I feel justified in talking about it because the likes of Time, Reuters, and TechCrunch all thought it was newsworthy. The study was small, so more work will have to be done to validate the findings on a wider scale. But the results are interesting. So, like Scrooge McDuck into his olympic-sized pool full of money, let’s dive in.

16 experienced coders were given 246 coding tasks to accomplish. Whether the coder was permitted to use generative AI was randomized. As a result, the researchers could compare the performance of coders by themselves to the performance of coders with the AI tools.

In addition to timing the tasks, the researchers also asked the participants what affect they thought the AI was having on the speed with which they performed the tasks. They asked them before completing a task, and then again after.

The results are pretty startling. Before completing the task, on average, participants expected the AI tool to reduce the time it takes to complete the task by 24%.

In the survey after the task, the participants were slightly less optimistic. Having already completed the task with the AI tool, on average, they thought the AI tool saved them only 20%.

But they were wrong—very wrong.

On average, the coders took 19% more time to complete the task with AI than it took them to complete it without.

Now, there could be any number of reasons that AI caused the coders to perform tasks more slowly. The authors of the paper suggest several possibilities. The coders might have been overly optimistic about the AI’s capabilities and, as a result, given tasks to the AI that they ought to have done themselves.

Or, it may be the case that because these were experienced coders, the AI just wasn’t as valuable as it might have been for inexperienced coders. In other words, if the researchers had run the experiment with novice coders, perhaps the AI would have saved those coders more time.

Then again, the authors also note that only 44% of the AI’s suggestions were adopted by the more experienced coders. So this finding might cut in both directions. On the one hand, maybe AI would be of more value—it would save more time—for novice coders. On the other hand, if only 44% of the AI tool’s recommendations were good recommendations, we might wonder whether the novice coders would be able to distinguish good AI recommendations from bad ones.

Finally, the authors suggest that one reason the AI slowed the coders down is that it lacked the tacit knowledge that the coders rely on—this sounds like a theme that runs right through the coverage of generative AI hallucinations.

I wrote about human intelligence as embodied intelligence—a lesson we can learn from Aristotle—in an earlier post. This feels like a symptom of that same problem.

The AI is not within the problem the coder is trying to solve in the same way that the coder is. So, it should come as no surprise that the AI tool either misses things the human coder wouldn’t miss or adds things the human coder wouldn’t add.

The big question the study raises is this: whatever it was in this study that caused the coders to take longer when using AI, is it the sort of thing we can fix; or is it the sort of thing we can’t fix. In other words, is it the kind of problem that either AI companies can solve with better tech or that users can solve through, for instance, better training with the tool or more experience with the tool? My answer: It depends.

For instance, suppose the most important factor that caused coders to take longer with AI really was their over-optimism about the tool’s capabilities. If so, then this is a user education issue. As these developers spend more time working with these AI tools, they’ll calibrate their sense of which tasks the AI can perform well and which tasks it can’t. Over time, as they lock in that calibration, AI performance will improve and the time to complete tasks will drop. But, in so doing, the experienced users will inevitably identify tasks that the AI can’t really help with. And in those cases, AI won’t improve coder efficiency. So, at best, AI will improve coder efficiency in some tasks, but not in all tasks.

But suppose the most important factor in the study was that the AI doesn’t have the tacit knowledge human coders have, and that tacit knowledge is a necessary condition for successful completion of coding tasks. If so, then, no amount of practice on the part of the coders will solve that problem. This would represent more of an inherent limitation in what (current) AI is capable of.

If you’ve been reading Views Expressed for any length of time, you are probably entirely unsurprised about my conclusion: LLMs represent an incredible leap forward in AI capability and they really will (and, for many, already have) changed the way we work. But unless and until the AI developers learn how to solve these problems—some of which increasingly seem to be inherent to the techniques used to train large language models—I just have a hard time imagining that we’re headed for the global disruption in work that many prognosticators have promised.

In AI as in oh, so many other things, I remain a radical centrist.

Credit where it’s due

I had seen a few headlines about the METR paper, but I probably would have let it slip by without comment if my dad hadn’t called to talk about how he’s incorporating generative AI into his undergraduate engineering curriculum. After that conversation, I dug a little deeper. He gets credit for this one.

Views Expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the US Air Force, the Department of Defense, or any part of the US Government.